Montreal has been growing continuously since the World Expo and the Olympic Games held in the 1960s and 1970s, while at the same time, the city has been destroyed. On the other hand, there is also a history of resistance to such modernization. In this series, Jin Motohashi, an architectural historian and Montreal resident, will report from Montreal on the city’s landscape, housing conditions, and relationship with the arts.

The second in the series will start from the Japanese Garden in Montreal Garden.

Recorded at the Japanese Garden in Montreal Botanical Garden

Location: 45°33’36.5″N 73°33’39.0″W

Date: June 6th, July 8th, 2022

The small monument in the park on Ave René Lévesque.

I am starting today’s story by introducing this small monument. This monument stands in a small park on Ave René Lévesque, across from a former high-rise of Radio Canada(45°31’03.2″N 73°33’13.4″W). This street is a bypass that runs parallel to Ave Saint-Catherine, which goes through the busy downtown area. Therefore, every car is passing at a fast speed. In the bustle of the city, a bronze plaque with the following engraved words stands quietly.

THE TREES ALONG DORCHESTER BOULEVARD, BETWEEN SAINT-URBAIN STREET AND PAPINEAU AVENUE, WERE DONATED BY THE JAPANESE MEMBERS OF THE MONTREAL BUDDHIST CHURCH (REV. TAKAMICHI TAKAHATAKE) AND JAPANESE BUSINESS FIRMS, AS AN EXPRESSION OF FRIENDSHIP TOWARD THE VILLE DE MONTREAL AND IN COMMEMORATION OF THE VISIT OF HIS EMINENCE LORD ABBOT KOSHIN OHTANI OF THE HONGWANJI TEMPLE, KYOTO, JAPAN…

The history of this street, written in French and English.

Most Rev. Koshin Ohtani was the 24th chief priest [門主] of the Hondan-ji school of the Jodo Shinshu sect, one of the most influential sects of Buddhism in Japan. This gift of trees started a project aiming to create a Japanese garden inside the Montreal Botanical Garden. In this essay, I will focus on the background story of the Japanese Garden in Montreal Botanical Garden and Ken Nakajima, a landscape architect and a central figure of this story.

Botanical Garden in Spring

“Flowers are falling, yet I will see them again when Spring returns. But, oh, my longing for the dear person who has departed from us forever!” (Takasue’s daughter)[1]

Even though I live far away from Japan, I still want to see cherry blossoms in spring. The flower heralds the arrival of spring; otherwise, I cannot wake up from cold winter. “Ah! I want to see cherry blossoms bloom!” I googled some cherry blossom spots in Montreal and got to know the existence of the Botanical Garden. Montreal is still chilly in mid-April. But I know of the fact that the time window for viewing the blossom is narrow. One famous Japanese Tanka, a kind of poem, says,

“Children, let us off to the hillside now,

To see the cherry blossoms at their play,

Delay not our going, for perhaps by the morrow

Their blithe little forms will have scampered away.”

(Ryōkwan)[2]

I quickly prepared Onigiri (rice balls) and Tamagoyaki (Japanese-style omelets) and my family headed to the Japanese Garden. The Botanical Garden is located in the north of downtown Montreal. Fortunately, it was close to our second apartment, so we could get there soon by bus.

The front building houses offices, a library, and archives.

Lucien Leroack, a Montreal architect, designed this Art Deco-style building in 1938.

The Chinese Garden. Le Weizhong designed this garden, which was constructed from 1990 to 1991.

The willows were beautiful and reminded me of the scenery of the West Lake in China.

Designed by Lucien Keroack in 1938, a large modern building with colored glazed tiles welcomes visitors at the entrance of the Botanical Garden. The Botanical Garden has several thematic areas, such as the Chinese Garden, English Garden, the Canadian old-growth nature, and so on.[3] The Chinese Garden was especially moving to me because it was very similar to the West Lake I visited five years ago in China. Speaking of West Lake, the area is famous for its tea production. I would have stayed in this spot for the whole afternoon if there had been a teahouse. After walking through the Chinese Garden, we finally got to the Japanese Garden. And we saw the cherry blossoms! It was almost lunchtime and my daughter was getting peevish because she was starving. We decided to have some Onigiri there.

Cherry blossom trees were planted one by one.

They were so beautiful and people were resting underneath.

“Let’s eat Onigiri in the warm spring sunshine.”

Japanese Pavilion for the 1967 Montreal Expo

Although these cherry blossom trees were not so big, we could feel the atmosphere of Hanami [お花見] once we sat under the umbrella of flowers. Both the designs of the Chinese Garden and the Japanese Garden did not feel kitschy, which is a quality we sometimes find in Asian-themed places created with exoticized images. When I contemplated that, one question emerged, “why is this Japanese Garden here?”

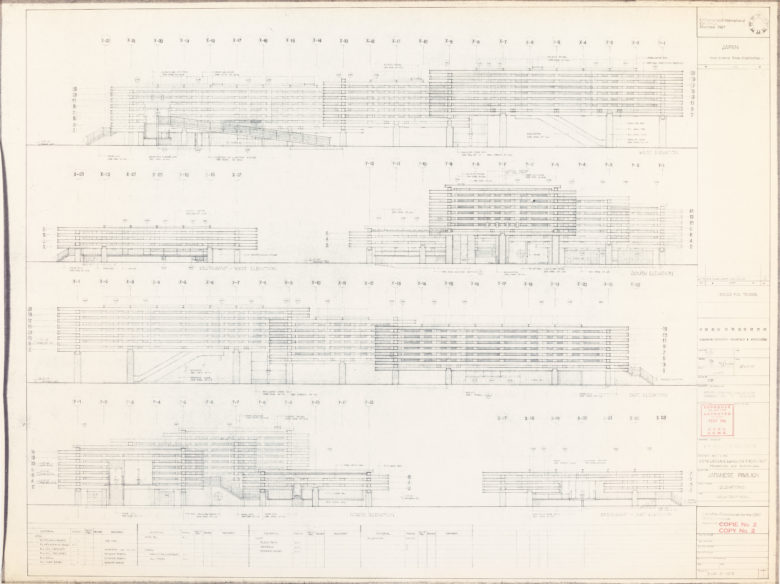

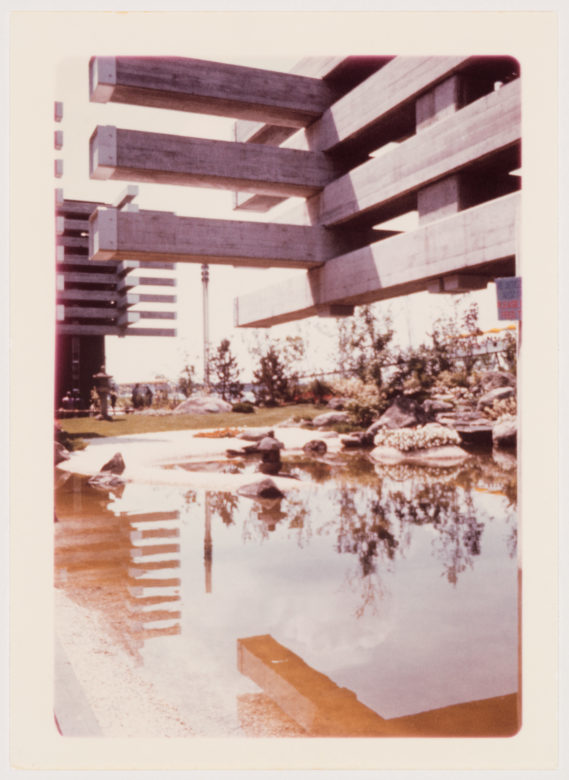

We must go back to the 1967 Montreal Expo to understand its history. Preceding the 1970 Osaka Expo, Montreal Expo attracted great attention from Japanese architects. Architect Yoshinobu Ashihara was in charge of designing the Japanese pavilion. He constructed a modern version of Azekura-zukuri using precast concrete and created a Japanese-style garden to fill the pavilion’s courtyard.

The Japanese Pavilion at Montreal Expo in 1967 and the Japanese Garden.

Courtesy of Yoshinobu Ashihara Architectural Archives

Yoshinobu Ashihara Architects┆Elevation drawings for Japanese Pavilion, Expo 67, Montréal,

Québec┆1966┆ARCH284056 Courtesy of Canadian Centre for Architecture

Partial view of the Japanese Pavilion, Expo 67, Montréal, Québec┆1967?┆ARCH261610

Courtesy of Canadian Centre for Architecture

View of the Japanese Pavilion, Expo 67, Montréal, Québec┆1967┆ARCH261714

Courtesy of Canadian Centre for Architecture

After the 1967 Expo, the calls for creating a Japanese-style garden in Montreal grew louder. At that time, the city mayor, Jean Drapeau, had already received schematic drawings of what later became the Japanese Garden inside the Montreal Botanical Garden. Jean Drapeau was the man who successfully brought the Expo and the Olympic Games to Montreal. However, time passed without progress in the plan to build the garden. According to reports, the Japanese garden, a feature created for the Japanese Pavilion, was left in its original place after the Expo ended. And, as I will explain later, some people were concerned with its unkempt state. Twenty years later, the project was finally put forward into motion. I want to introduce the following story described in an article[4] written by Mr. Pierre Bourque, the 40th mayor of Montreal and a botanist of the Botanical Garden at that time.[5] He studied horticulture in Belgium and he had been involved in the renewal of the Botanical Garden since 1980.

Takahiro Takahatake and 100 Trees Plantation

In 1984, the process moved forward. The project was propelled by the tree planting event described at the beginning of this essay. The person who organized this tree planting was a Japanese Buddhist monk named Mr. Takamichi Takahatake. He was born in Takaoka city, Toyama prefecture, in 1941. He majored in religious studies and graduated from McGill University in Montreal. He continued to live in the city after graduation. One day he visited the Botanical Garden and the Montreal City Hall. The purpose of his visits was to consult about a request related to Rev. Koshin Ohtani’s trip to Canada. Rev.Ohtani was the 24th head priest of the Hongwanji sect of Shinshu Jodo and had the plan to travel around Canada, including Montreal, in 1984.

In 1905, Jodo Shinshu started the missionary program in Canada. According to the newspaper “Hongwanji Shimpo,”[6] the Shinshu Jodo sect organizing the trip said that the primary purpose of Rev.Ohtani’s trip to Canada was to celebrate the program’s 80th anniversary. They planned a three-week tour from the 24th of October to the 13th of November, 1984, stopping at 17 Buddhist churches. The tour began in Vancouver and went on to Kelowna, Winnipeg, Montreal, and Toronto.

“The head of the missionary will come to Montreal.” This must have been a big deal for the followers living abroad. So, Takahatake must have felt a strong desire to do something special to welcome Rev. Ohtani in Montreal. He succeeded in planting 100 trees along Ave Rene Lévesque to commemorate the occasion and held an opening ceremony in November 1984.

This experience inspired him to pursue the goal of creating a Japanese garden in Montreal. At first, he dreamed of adding several functions to the garden, including a library, gallery, tea house, and meeting room. The project began to take shape little by little, but it took great effort. One reason was the garden that he planned to use as a foundation for this project had been abandoned after the Expo. The situation made Japanese people in Montreal skeptical of the city’s management. Therefore, it was not easy to obtain local cooperation.

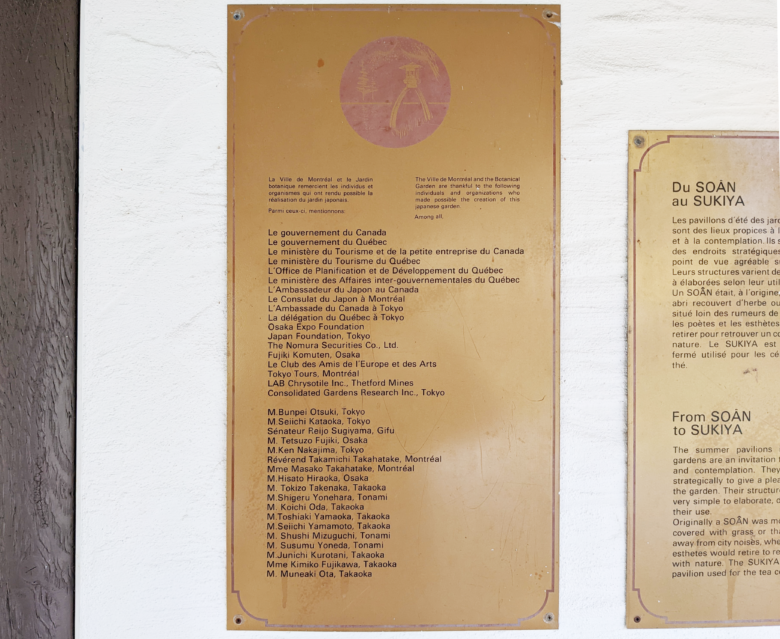

Takahatake approached Seiichi Kataoka, a member of Japan’s House of Representatives, to become his collaborator. The reason was that they were both from the same town in Japan, and Kataoka was an official elected by the people living in their hometown. When Kataoka visited Montreal for work as a member of the Diet, Takahatake introduced Mr. Pierre Bourque to him. Pierre’s memoir indicated that Kataoka took the trouble to pick up his camera from his hotel room so that he could take a group photo. Pierre interpreted Kataoka’s gesture as a firm commitment to the project. After the trip, Kataoka found investors in Japan for this project, and finally, in 1987, a ceremony was held to celebrate the opening of what is now the Japanese Garden in the Montreal Botanical Garden.

The Japanese Garden in Summer. Carp swim in the pond.

The sound of the falling water echoes in the garden.

The view of the Olympic Stadium from the Japanese Garden.

Ken Nakajima sometimes directed the landscaping team from the top of the tower.

The panel lists the name of donators, including Seiichi Kataoka and Ken Nakajima.

Isoya Yoshida, the Architect’s Collaborator

While eating Onigiri, I wondered who designed this beautiful landscape. A google result led me to find it was Ken Nakajima. I soon learned that he was an essential collaborator to an architect, Isoya Yoshida.[7] I did not know much about Japanese gardens, but I realized that I could begin learning if I started where I specialized: architecture. My curiosity about Yoshida’s career grew.

Landscape architect Ken Nakajima in the Japanese Garden in Montreal

Archives de la Ville de Montréal┆VM94-J0663-004

Architect Isoya Yoshida. Most of those who studied architecture in Japan know of his name. It made sense to me. Naturally, architecture like Yoshida’s needs a landscape architect. Until now, I had not thought about landscape architects when looking at architecture. It seemed Nakajima often worked with Yoshida throughout his career.

Ken Nakajima was born in Tokyo in 1914. Upon entering Waseda University Second Senior High School, he began studying horticulture. He graduated from Tokyo Zoen High School in 1937 with a plan to continue his study at a horticultural school in Versailles. Nakajima visited Kyoto University to consult with Ayaakira Okazaki, who had just returned to Japan after studying horticulture in Germany. Nakajima also met Shuji Hisatsune there, and this meeting changed his life.[8]

“Please help me create a survey map of a garden in Kyoto,” Hisatsune requested Nakajima. At that time, Hisatsune was documenting Japanese gardens damaged by the first Muroto Typhoon of 1934. He took Nakajima to the Saiho-ji Temple (Hisatsune was later involved in this temple’s restoration work). While working on the survey, Japan entered into WW2 and Nakajima was drafted. After the War, he was asked to design a garden for Minoru Yamasaki’s U.S. Consulate General in Kobe (1956) through Tokuzaburo Kimura, an architect from Obayashi Corporation.

Consulate General of the United States, Kobe

Architect: Minoru Yamasaki Contractor: Obayashi Corporation

Courtesy of Obayashi Corporation

Consulate General of the United States, Kobe

Architect: Minoru Yamasaki Contractor: Obayashi Corporation

Courtesy of Obayashi Corporation

He worked on the landscape planning for then-prime minister Shigeru Yosida’s residence. This house is known as one of Isoya Yoshida’s most notable projects. He designed the new addition, and the reception room[9] was designed by Tokuzaburo Kimura. On this project, Isoya Yoshida befriended Nakajima. Nakajima went on to create the gardens of The Japan Art Academy Hall (1958), the Gyokudo Art Museum (1961), and The Japan Cultural Institute in Rome (1962)[10]. All of these are known as masterpieces of Isoya Yoshida.

Shigeru Yoshida’s residence (completed in 1961 and rebuilt in 2016), Architect: Isoya Yoshida

Courts of Takahiro Ohi

Gyokudo Art Museum (1961), Architect: Isoya Yoshida

Courts of Takahiro Ohi

Creating Japanese Gardens Abroad

Nakajima was in Rome for one year on a business assignment and was working on Yoshida’s project for the Japanese Cultural Institute in Rome. While in Rome, he contemplated whether to incorporate Western flowers into a Japanese garden. However, he also realized Western flowers did not look attractive if included in a strictly orthodox Japanese garden. This realization motivated him to explore ways to pair Western and Japanese elements effectively. After his time in Rome, he received more opportunities to participate in projects overseas, including Austria, New Zealand, Hungary, the Soviet Union, West Germany, and the Czech Republic. He also had many chances to make presentations and create Japanese gardens continuously. He became known as a Japanese landscape architect overseas. His major works are in Hermann Park, Houston, the Royal Norwegian Embassy, Cowra, Australia, Moscow, and Montreal. Over twenty of his gardens are in foreign countries.

Cowra Japanese Garden

Courts by Cowra Japanese Garden & Cultural Centre

Ken Nakajima’s Philosophy on Japanese Garden

Besides creating the gardens, he also trained many to become his successors.[11] The landscape architects who later became well-known, such as Yoshikuni Araki and Takushi Inoue, were his apprentices before the war. Kotaro Terada and Tsuguo Sekita, who later created Asahiyama Zoo, were trained by Nakajima after the war. Nakajima’s firm also produced Kiyoshi Nozawa. Nozawa collaborated with many architects. For example, he worked with Syozo Uchii to create the gardens of the Setagaya Art Museum (1986) and Hasegi Memorial Museum (2000). With Hisao Koyama, he designed the gardens of the Soga Memorial Museum (1991) and Nagakute-Cho Cultural House (1998). He collaborated with Yoshiro Ikehara on the gardens of the Sakata City Art Museum (1997) and the Kameoka Galleria (1998).。

The previous study[12] cited that most landscape architects who studied under Ken Nakajima designed with precision and delicate sensibilities. It is noted that “they have a great aesthetic sense for spatial composition, such as emphasizing the slightest tumble or rise of rocks. Even when cutting a horizontal architectural line with a vertical line of a tree trunk, they would make it stand slightly oblique. And they pay attention to ways to embed oblique elements in their designs.”

The photo of the Japanese Garden under construction.Red bricks and concrete blocks support a single block of natural rock. The orientation of the rock was carefully adjusted.

Mise en place des pierres JBM-J-24-165. 25 sept 1987 Photo N. Rosa

Archives – Jardin botanique de Montréal

I am curious how Nakajima achieved creating Japanese gardens of his ideal abroad. In search of a hint to this question, I found out that the Montreal Botanical Garden had a library. I contacted them, and soon the reply came back to me. The email said kindly, “we have materials of the Japanese Garden in our archives, too.”

Shortly after that, I was in the library, examining archived photos. Some of them were very moving to me. I had my eyes glued to one picture. It showed a moment before the start of the construction. There were no waterfalls, hills, ponds, or fish in it. It was just flat land. The photo reminded me that the Japanese Garden was artificial. Although it was obvious if you think about it, I was amazed by the fact that this artificial natural environment was created from scratch. At the same time, I also learned about many difficulties Nakajima faced in the making of this garden from several documents. Yes, Japanese gardens need rocks. Natural rocks. But from where? Let’s look for these rocks!

The construction site of the botanical garden. The Olympic stadium is shown in the background.

The flat grassy plaza was about to be built with heavy machinery.

Archives – Jardin botanique de Montréal

[1] Sugawara no Shikibu Murasaki and Shikibu Izumi. 1920. Diaries of Court Ladies of Old Japan. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

[2] Fischer Jakob. 1937. Dew-Drops on a Lotus Leaf. Tokyo: Kenkyusha.

[3] L’Enclume, Recherche documentaire préalable à l’énoncé patrimonial du Jardin botanique de Montréal, 2019.

[4] Pierre Bourque, The Japanese Garden: A Marvellous Adventure, Quatre-temps, vol.12 no.2, 1988, pp.8–15.

[5]Pierre Bourque was born in Montreal in 1942. He studied horticulture in Belgium. And he was in charge of the Montreal Expo in 1967. Since 1969, he has been a member of the Botanical Garden. He worked on the Japanese Garden, the Chinese garden, the Insectarium, and the Biodome. He then entered municipal politics in 1994 and served as mayor until 2001.

http://www2.ville.montreal.qc.ca/archives/democratie/democratie_fr/expo/maires/bourque/index.shtm

[6]Hongwanji Shimpo. No.2165. 1984.

[7]The following two books detailed Ken Nakajima’s represented works. 1) Ken Nakajima’s Works (private edition) in the collection of Botanical Garden. 2) In Memory of Ken Nakajima. Landscape Design. June 2001. pp.118–129.

[8]Ken Nakajima. Report Bringing the Japanese Garden to the World: The Path Taken by Landscape Architects. Bulletin. January 1998. Vol. 122. The Japan Institute of Architects (JIA) Kanto Koshinetsu Branch. pp.8–9

[9]Moe Kuboniwa. Reconstruction and opening to the public of the former residence of Shigeru Yoshida. Kyodo Kanagawa. March 2018. Vol. 56. Kanagawa Prefectural Library. pp. 44–49.

[10]The Japanese Cultural Institute in Rome. Kenchiku-Bunka. July 1963. Vol.17 No. 201. pp. 113–116.

[11]Takashi Awano, Makoto Suzuki. Modern Landscape Designer and Formation of their School in Postwar Japan. Journal of the Japanese Institute of Landscape Architecture. July 2012. Vol.76 (2) pp. 127-130.

[12]Same as above.

—

I want to thank the following people for their assistance in writing this article. The Japan Institute of Architects (JIA) Kanto Koshinetsu Branch, Jardin Botanique de Montréal, Obayashi Corporation, U.S. Consulate General in Osaka-Kobe, Taro Ashihara Architects, Takahiro Ohi of Mie University, Akira Kikuchi of Kyoto University, Shuntaro Kondo of Honganji Shiryo Kenkyujo, and Canadian Centre for Architecture.

Translation┆Jin Motohashi

English proofreading┆Fraze Craze Inc.

*All photos were taken by the author unless otherwise noted.